What has corruption to do with cross-border secrecy?

Financial secrecy is a key facilitator of corruption. Without financial secrecy, many corrupt deals simply would not be able to happen.

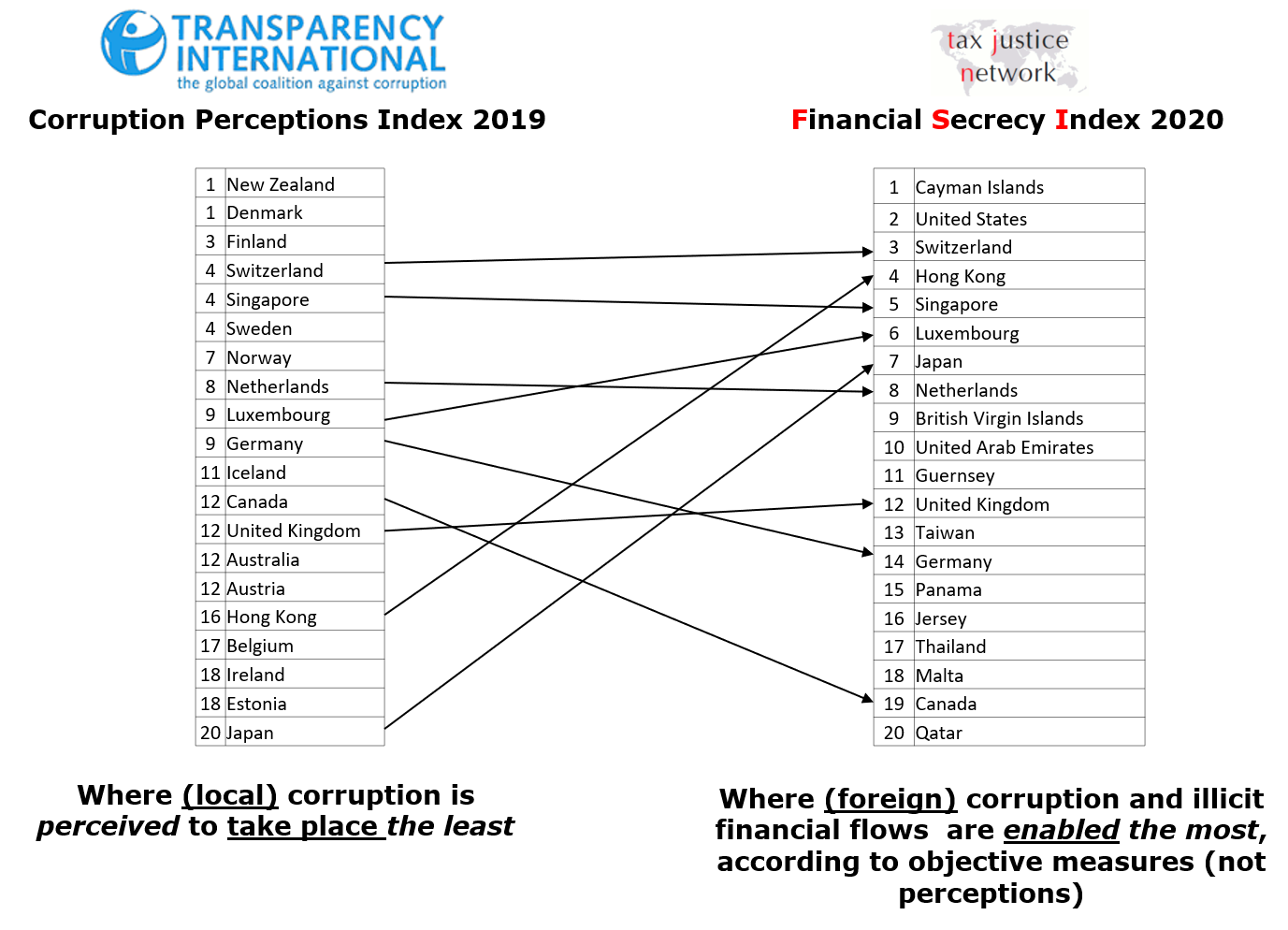

In the field of international governance and transparency, one of the most well-known rankings of corruption is Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index. The Corruption Perceptions Index ranks poor countries in Africa and elsewhere – predominantly the victims of an estimated US$1 trillion-odd in annual illicit financial outflows – as the ‘most corrupt’. But all these outflows must be received somewhere. So the Financial Secrecy Index examines the enablers: those jurisdictions that encourage and facilitate illicit financial flows, by providing an environment of secrecy that allows these outflows to remain hidden, and largely untaxed.

As a comparison of the two indices shows below, the Corruption Perceptions Index ranks jurisdictions by perceptions (see here for a critique of this methodology that focuses mainly on so-called experts and local elite views) where local corruption is the worst. In this way, as Alex Cobham wrote in Foreign Policy, the Corruption Perceptions Index “embeds a powerful and misleading elite bias in popular perceptions of corruption, potentially contributing to a vicious cycle and at the same time incentivizing inappropriate policy responses”.

In contrast, the Financial Secrecy Index uses objective measures (not perceptions!) to examine which countries are the worst offenders in enabling corruption and illicit financial flows from other countries. What you see is that many countries perceived to be the least corrupt by their citizens are actually among the worst offenders in enabling corruption and illicit financial flows in other countries.

So now what? Should we focus on the top, most rich countries enabling corruption or on those poor ones suffering from it? While the Tax Justice Network hopes that all countries will become more transparent and address all sources of illicit financial flows, the key solution is to stop the top countries, who tend to set the international agenda given some of their colonial histories of exploitation, from enabling corruption everywhere else in the world.

As long as tax havens and secrecy jurisdictions keep offering banking secrecy and the ability to hide other assets (real estate, gold, art), or the identities of criminals behind secretive companies, trusts, partnerships or foundations, it will be impossible – both for poor countries and for rich ones – to stop the suffering resulting from corruption, tax evasion, money laundering and other financial crimes.

As Transparency International itself acknowledges, “However, integrity at home does not always translate into integrity abroad, and multiple scandals in 2019 demonstrated that transnational corruption is often facilitated, enabled and perpetuated by seemingly clean Nordic countries”.

If you had the chance to improve the laws and regulations of 10 countries, what do you think would have more impact in stopping corruption and other financial crimes in the world? Fixing corruption in the countries perceived to be the most corrupt – Somalia, South Sudan and Syria? Or making sure that the Cayman Islands, the US, Switzerland, and others no longer offer the secrecy that enables corruption, tax evasion or money laundering in the rest of the world?

Businesses looking to invest overseas may find it useful to know that the Corruption Perceptions Index ranks Libya, say, as among the world’s most corrupt nations from the perspective of officials demanding bribes. But this is of little help to ordinary Libyans, who want to know more: where their country’s wealth has gone, how it left, and who helped it leave. This is where the Financial Secrecy Index comes in. We consider the former Libyan leadership to represent the demand side of corruption, while Zurich, London, and other secrecy jurisdictions that received illicit Libyan loot to be the suppliers of corruption services: the supply side.

The same challenge faces Angolans. The Luanda Leaks uncovered how former Angolan president’s daughter Isabel dos Santos bought state assets and made use of more than 400 companies, subsidiaries and accounts in 94 secrecy jurisdictions. This business empire benefited to the tune of many billions of dollars in consulting jobs, loans, public works contracts and licenses from the Angolan government. The Financial Secrecy Index ranking reveals what the Corruption Perceptions Index conceals. It exposes the hypocrisy that lies behind some of the finger-pointing at “highly corrupt” developing countries, and provides a basis for a new wave of understandings about corruption in a global context.

Read more about corruption, financial secrecy and tax justice here.