What roles do the UK and USA play?

The British connection

Various OECD member states run satellite secrecy jurisdictions, but Britain’s network is by far the largest, accounting for between a third and a half of the global market in offshore financial services. Ten secrecy jurisdictions on our list are either British Crown Dependencies (Jersey, Guernsey, the Isle of Man) or British Overseas Territories (such as the Cayman Islands, the British Virgin Islands or Bermuda). These places, the last official remnants of the British Empire, are supported and controlled by the UK, though they each have different political systems and a measure of political autonomy. Outside this group lie a series of 15 British Commonwealth Realms and 53 British Commonwealth countries, which include some Overseas Territories but otherwise have a much looser relationship with the UK.

All these jurisdictions generally share British common law; deep financial penetration by British financial interests and enablers; they typically use British-styled offshore structures such as trusts; they usually have English as a first or second language; and most of them have their final court of appeal at the Privy Council in London: a legal bedrock that reassures investors and underpins their offshore industries.

The Queen is head of state in most of these territories and in the Crown Dependencies and Overseas Territories she appoints top officials including the governor; and her head appears on their stamps and banknotes. Britain has wide powers that allow it to disallow or change their secrecy legislation, though as our UK narrative report explains these powers are not straightforward, and Britain has generally chosen not to exercise its powers for political and economic reasons.

The British network has for decades served as a global 'spider's web' network capturing financial business from countries around the world and feeding it into the City of London. Jersey Finance, the official body representing that secrecy jurisdiction's financial services industry, illustrates this with a statement that "Jersey represents an extension of the City of London." This network, among many other things, allows the City to get involved in dubious financial businesses at arm's length, and to avoid responsibility when scandal strikes.

Has the UK cracked down?

In the Financial Secrecy Index 2020, the UK increased its secrecy score more than any other country. While countries on the Financial Secrecy Index on average decreased their secrecy scores by 3 marks out of 100, the UK increased its secrecy score by 4 marks, from 42 to 46 out of 100.

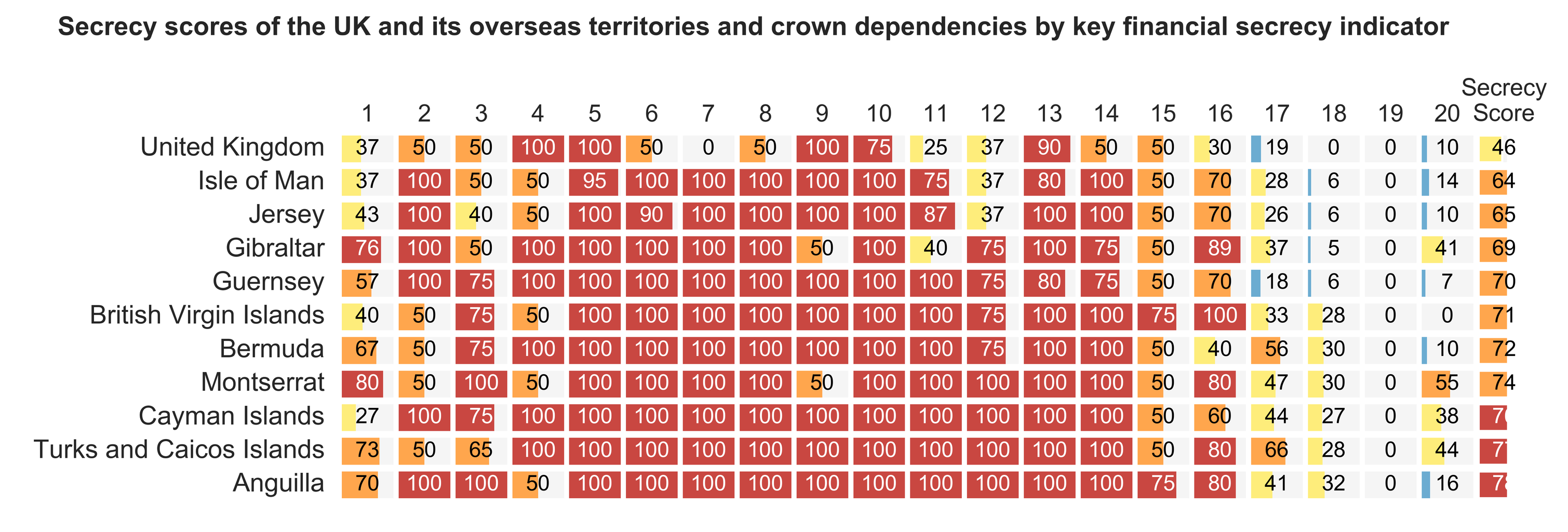

The British government still continues to protect the status of the Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies where much of the dirty business is done before the money reaches the City of London, as illustrated in the chart below. The UK’s spider’s web included some of the highest ranking jurisdictions on the Financial Secrecy index, including the Cayman Islands, which ranked first, the British Virgin Islands which ranked 9th and Guernsey which ranked 11th. The satellite jurisdictions that make up the UK’s spider web on average increased their supply of financial secrecy to the world by 17 per cent, which is more than double the rate at which countries around the world on average reduced their supply to global financial secrecy. If the UK and its network of Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies were treated as a single entity, this UK spider’s web would rank first on the index.

Each indicator is explained here.

The UK government has refused to impose more financial transparency on these territories, especially with regard to trusts. To the contrary, it has actively protected them from international scrutiny, for example, by lobbying to remove them from the EU’s list of tax havens released in 2017. Efforts by British parliamentarians to require Crown Dependencies to make their beneficial ownership registries public have been stymied, most recently in March 2019. Guernsey, Jersey and the Isle of Man have now agreed to bring legislation before their parliaments to make registers public, but only by 2023.

The UK’s post-Brexit strategy is also to be watched. With a marked escalation of the UK’s contribution to global financial secrecy by 26 per cent, the strategy to turn London into the ‘Singapore-on-Thames’ should be on the radar of especially EU countries which collectively reduced their contribution to global financial secrecy by 8 per cent.

The chart below illustrates the changes in secrecy score since 2018 edition of the financial secrecy index, revealing that the majority of jurisdictions in British spider’s web have increased their secrecy scores, becoming more secretive, since 2018.

The United States

The United States, ranked in second place in our 2020 index, started deliberately turning itself into a secrecy jurisdiction during the Vietnam War, as a way of attracting capital to fill its expanding external deficits. As our US narrative report explains, these secrecy facilities were intentionally established at the federal level as well as by individual states. For example, Delaware and Nevada offer powerful secrecy through corporate vehicles incorporated in those states.

Today the United States is perhaps the jurisdiction of greatest concern, in terms of global financial transparency. The US remained second on the 2020 edition of the Financial Secrecy Index and further increased its contribution to global financial secrecy by 15 per cent. It may remain second, but it’s now overtaken Switzerland. The US’s increased contribution is primarily a result of its worsened secrecy score, largely attributed to the passing of a new law in New Hampshire permitting the establishing of non-charitable private foundations without the need for disclosure.

This is part of a worrying trend. The US has been steadily rising up the rankings of the Financial Secrecy Index. It moved from 6th place in 2013 to 3rd in 2015 and then up to 2nd in 2018, where it remains in 2020, but with a higher secrecy score.

While the US has taken major steps to protect itself against tax evasion through foreign tax havens – not least through its willingness to arrest Swiss bankers and open up the Swiss secret banking establishment, and through its feisty Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) to hunt down US taxpayers' assets overseas. But it has been very reluctant to share information in the other direction: residents of other countries have stashed trillions of dollars' worth of assets in the US, secure in the knowledge that the US refuses to take part in international initiatives to share tax information with other countries.

The US has so far failed to meet ambitions announced last year by Senator Lindsey Graham at a senate committee hearing to improve its ranking on the Financial Secrecy Index. The US has also failed to end anonymous companies and trusts aggressively marketed by some US states. There is now real concern about the damage this promotion of illicit financial flows is doing to the global economy.

However, there is some room for optimism since there is some bipartisan recognition of the problem. For example, in October 2019, the US House of Representatives passed a bipartisan measure — the Corporate Transparency Act — in October to end the abuse of anonymous companies and similar legislation, known as the ILLICIT CASH Act, is being considered by the Senate Banking Committee.

See more in our US country report.